The Dystopia is Now:

An Interview with Maurice Carlos Ruffin

by Karin Cecile Davidson

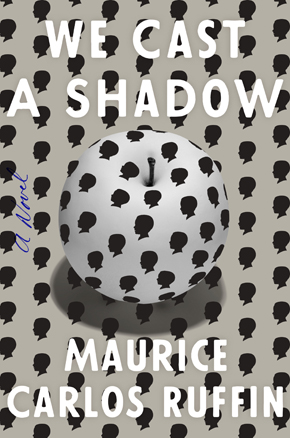

In New Orleans’ author Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s much acclaimed debut novel, “We Cast a Shadow,” we find ourselves in a near-future southern city, where white supremacy reigns and the process of “demelanization”—a medical procedure to remove all characteristics of blackness—has become popular. Our unnamed Narrator, a black lawyer at a white-glove firm, is obsessed with the possibility of advancement in order to afford this procedure for his biracial son. In his desperation, he strives to protect his son from racial violence, and yet, it becomes clear that he has fallen into the trap of this very same violence by pushing this “protection” onto his son. As Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah writes in his New York Times review of “We Cast a Shadow,” “The Narrator shows us over and over again what happens when love is pushed out into the world from a source that does not love itself. That kind of love looks and feels a lot like violence.” Sweeping ideas of inheritance, pride, injustice, humanity standing back-to-back with inhumanity, survival, and devotion swarm and abound in these pages. Language that flies, whip-smart and stunning, uncovers a cracked and unjust society and calls up moments of magnified family love.

In New Orleans’ author Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s much acclaimed debut novel, “We Cast a Shadow,” we find ourselves in a near-future southern city, where white supremacy reigns and the process of “demelanization”—a medical procedure to remove all characteristics of blackness—has become popular. Our unnamed Narrator, a black lawyer at a white-glove firm, is obsessed with the possibility of advancement in order to afford this procedure for his biracial son. In his desperation, he strives to protect his son from racial violence, and yet, it becomes clear that he has fallen into the trap of this very same violence by pushing this “protection” onto his son. As Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah writes in his New York Times review of “We Cast a Shadow,” “The Narrator shows us over and over again what happens when love is pushed out into the world from a source that does not love itself. That kind of love looks and feels a lot like violence.” Sweeping ideas of inheritance, pride, injustice, humanity standing back-to-back with inhumanity, survival, and devotion swarm and abound in these pages. Language that flies, whip-smart and stunning, uncovers a cracked and unjust society and calls up moments of magnified family love.

Winner of an Iowa Review Award in fiction and a Faulkner-Wisdom Creative Writing Competition for Novel-in-Progress, Maurice Carlos Ruffin is a graduate of the University of New Orleans Creative Writing Workshop and is a member of the Peauxdunque Writers Alliance. His work has appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, AGNI, The Kenyon Review, The Massachusetts Review, and Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas.

My name doesn’t matter. All you need to know is that I’m a phantom, a figment, a man who was mistaken for waitstaff twice that night.

—Maurice Carlos Ruffin, “We Cast a Shadow”

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: The first lines of “We Cast a Shadow” introduce the nameless Narrator and set the stage for how he identifies himself: unrecognized, unrealized, a specter and an illusion, lost inside a skin that he himself rejects by novel’s end. He’s a tragic figure, split into opposing selves: a devoted and loving father and husband, a lawyer who bends and applies himself to the machinery of white supremacy. He understands the dilemma and still flies forward into the machine, despite all that he will lose—his family, his humanity, his soul.

Maurice, how did you discover this Narrator? His crisp dramatic voice, his unrelenting direction, his manner of observation, and his droll, yet disastrous sense of the world?

MAURICE CARLOS RUFFIN: I had been writing vignettes with this character for years. But one night I was toying with that opening scene and—I don’t know how else to describe it—there was a quickening. The Narrator’s voice went from two-dimensional to lifelike and autonomous. I can’t explain it other than to say it is the magic of writing. From that point, he directed my research, steered the narrative, and gave me a new framework for viewing the world.

There was something about that shadowless afternoon … I wasn’t particularly religious, but I noted brief sequences of my life where the invisible medium—air, mist, water, I could never say what the medium most resembled—seemed to drain away. In those moments, there was nothing at all between me and them, the two souls I cared about in all the knowable universe.

—Maurice Carlos Ruffin, “We Cast a Shadow”

DAVIDSON: Family seems the foundation of the Narrator’s world, and yet he does everything in his power to set a course for tearing it down and then apart. He seems incredibly aware of the peace and love found within his life with his wife Penny and son Nigel, and simultaneously blind to the purposeful direction that ultimately leads to his family’s destruction.

Speak to us about family within the novel, how a man, whose love for his immediate family is practically electric, can choose to short-circuit everything wonderful in his life.

RUFFIN: The Narrator is like so many people. He’s bedeviled by trauma. Trauma can make us forget what’s most important and take actions that are ultimately self-destructive. It’s the story of humanity. You would have a hard time finding anyone who isn’t operating under layers and layers of generational and societal trauma.

That black medallion of skin on his tummy is bigger. Nigel’s other blemishes cover his body. The greatest concentration of marks: belly and back. A dark asterism. Some flaws approach the size and complexity of the stigma on his face. Some discolorations have undergone transmutations similar to the facial mark. Some even seem to have moved over time from one hemisphere of his body to another. My fear is that these islands will merge to form a continent. The lesser smudges, they’re just ordinary freckles. But what image would emerge if I traced those dots. His mother? Our home?

—Maurice Carlos Ruffin, “We Cast a Shadow”

DAVIDSON: Blemishes, flaws, stigma, discolorations, smudges. The language the Narrator uses to describe his son’s body, his blackness, stings, and the negative connotations of the descriptions are startling. Over 100 pages into the novel, this shouldn’t be surprising, and yet it is. It becomes very clear that the Narrator’s attitude is unchanging, that he’s driven by fear and is well on his way toward losing his sense of himself as a father, much less his sense of humanity. He can dull down his anxieties with “Plums” and “Blue Geishas,” his drugs of choice, but he still must answer for his decisions in the long run.

The thought at the center of the Narrator’s mind and at the center of this novel, “a dark-skinned child can expect a life of diminished light,” sets the tone and course of action. The novel’s near-future world, in which race relations have dramatically descended, in which it is dangerous to live in a black body, greatly resembles the world in which we actually live.

As a writer and a lawyer, as a black man living in the South, would you tell us more about the keenly perceptive view of race in America that you’ve presented here?

RUFFIN: Thank you for that. I didn’t have to make anything up. I simply looked at the world in which we live and selected from available incidents. There are no aliens, time-travelers, vampires, or superheroes in my book. Yet, the incidents feel dystopian, don’t they? That tells us the dystopia is now. Virtually everything in the book has or does exist in some time or place. That was the challenge I gave myself. For example, there are plenty of fenced in ghettos all around the world today. They were also built in Nazi Germany and in Italy in the Dark Ages.

“Whatever happens, you can’t give in to them, because then you’ll have nothing left,” Sir said … His face was slick. It occurred to me that I’d never seen my father cry. I’d never seen any man cry.

—Maurice Carlos Ruffin, “We Cast a Shadow”

DAVIDSON: Fathers and sons. Thematically central, and in terms of the Narrator’s relationship with his father, a vastly significant complication. On the one hand, there is Nigel, a son to protect, and on the other, Sir, a father who tried to protect his family and was imprisoned for his attempts. From life on the outskirts of the Tiko, a high-density housing project, to life inside Buckles Correctional and Liberia, the City Prison, Sir becomes yet another body trapped in the maze of mass incarceration.

The arts continue to examine and explore how our country was founded on slavery and how the mass incarceration of black men and women has kept this brutal and exploitive system alive. Along with novels and poetry collections, film and opera have also created this critical dialogue. What is your sense of how “We Cast a Shadow” contributes to this conversation?

RUFFIN: If you look at any period in American history, artists, writers, and activists like Phyllis Wheatley, Ida B. Wells, Loraine Hansberry, Audre Lorde, Octavia Butler, etc., were doing the work to investigate and interrogate the many aspects of white supremacy. I simply wanted to join hands with those who preceded me and those who are working now. Readers have said the book does this well.

DAVIDSON: “We Cast a Shadow” is structured in four parts, the first introducing conflict and characters and the final revealing a new generation, one that moves on without the Narrator, evolves without him. In his unchanging attitude, on queue with everything he has achieved, he loses everyone and everything, and this is certainly not without despair. There is a remarkable brilliance to this choice of four acts.

DAVIDSON: “We Cast a Shadow” is structured in four parts, the first introducing conflict and characters and the final revealing a new generation, one that moves on without the Narrator, evolves without him. In his unchanging attitude, on queue with everything he has achieved, he loses everyone and everything, and this is certainly not without despair. There is a remarkable brilliance to this choice of four acts.

How did you decide on the novel’s configuration? Did the Narrator lead, or was there a more formal way of composing that you followed?

RUFFIN: As a writer, I’m completely driven by character, so the Narrator led the way. The four-act structure was his construction as it represents four shifts in the way he sees himself. That being said, “Lolita” and “Invisible Man” provided some structural guidance as well.

I’d never been to Shanksted Plantation … I’d never done a double-take at a gleaming white chateau with shadowy, Dracula-teeth columns. I’d never ridden up a rustic promenade, across the same twigs and pebbles over which somebody’s barefoot mom had once hauled kindling.

—Maurice Carlos Ruffin, “We Cast a Shadow”

DAVIDSON: Place in “We Cast a Shadow” is impressive—“The City,” “the Avenue of Streetcars,” Octavia Whitmore’s mansion, “Shanksted Plantation,” “the Sky Tower,” “the Tikoloshe Housing Development,” Buckles Correctional, and Liberia. In this world, the architecture of place is that of white supremacy.

In considering the concept of physical spaces that close in and exclude, and from the novel’s structure to the actual structures within the novel, tell us about the process of creating this deeply symbolic world.

RUFFIN: Place is everything in the book. From the Sky Tower, which is literally a big, white obelisk, to the Plantation, which hasn’t changed much in centuries. But just like with the incidents of the novel, I didn’t have to be that imaginative with the locations. I had plenty of real-world places to choose from. There are so many gleaming skyscrapers in New Orleans, which is a majority-black city. But the black professionals in those buildings are outnumbered perhaps 33 to 1.

The past is a shipwreck.

—Maurice Carlos Ruffin, “We Cast a Shadow”

DAVIDSON: In the novel’s audio-book version, actor Dion Graham (of the series “The Wire”) provides a dramatic depth and resonance in his reading that, for me, gives the Narrator and other characters interesting dimensions which I hadn’t perceived when I read the book on my own. With the dramatization of the voices, I understood a new kind of sadness within the Narrator toward the end of the book. He remains conflicted, knowing well the destructive legacy he’s handed down to his son, yet still wishing a better life for his granddaughter. What is your impression of this reading, especially in terms of your characters?

RUFFIN: Dion shocked me, too! A great actor can add so much to the text. The tenor and tone of voice. The variation of cadence and emphasis. I felt a whole slate of fresh emotions that he drew from me. I’m so happy the audiobook was produced, and I’m especially happy Dion was available. I literally laughed and cried at his performance.

DAVIDSON: The writing in “We Cast a Shadow” has been compared to that of Ralph Ellison, Vladimir Nabokov, and Franz Kafka. Jesmyn Ward and Toni Morrison also come to mind. Where do you find those that inspire and influence you? Tell us about your literary community and what you have in mind in terms of future writing.

RUFFIN: Like any writer, the work of great writers is the air I breathe. I read as widely as I can. I couldn’t have written the book without the writers I look up to, including my local writing community in New Orleans. They have supported me in more ways than I can count. A lot of writers passed through New Orleans in the past, including Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote, but I have hope that our current community will make a durable place for itself in the literary world. As for my future, I plan to write everything I can. A short story collection is on the way. I’ll do an essay collection. I’ll write a screenplay at some point. Definitely another novel or 10, if I’m lucky. I’m a writer. I write. It’s really the only thing I do that leaves a mark.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor