A Music Plucked Out of Happiness:

An Interview with Diannely Antigua

by Karin Cecile Davidson

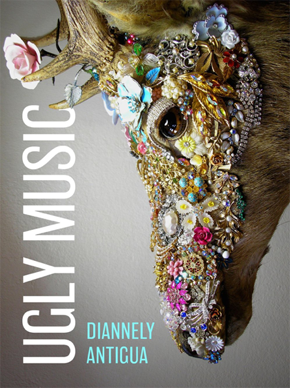

In Dominican American poet Diannely Antigua’s debut collection “Ugly Music” (YesYes Books, 2019), winner of the Pamet River Prize, one finds sources of despair, ecstasy, and sheer honesty cracked and threaded with lyrics, breath, and tears. Mothers, grandmothers, stepfathers, and lovers enter and exit the pages, while the poems’ speaker sings and shouts and whispers words of violence and love, sex and loss, grief and drowning, miraculous surrender and rescue, forgiveness and faith. Structured as a song, with verse and chorus leading to bridge and ending in outro, the collection is shaped from memory, family, and diary entries and layered with distant islands, children lost, backseats and pregnancy tests, self-love and God’s work. As author Catherine Barnett writes, “Diannely Antigua’s “Ugly Music” is a beautiful disturbance of erotic energy … [a] seduction both intellectual and physical … [and] at its deepest song … a theological protest and investigation by a speaker wrestling with faith and fathers, with unapologetic desire.”

In Dominican American poet Diannely Antigua’s debut collection “Ugly Music” (YesYes Books, 2019), winner of the Pamet River Prize, one finds sources of despair, ecstasy, and sheer honesty cracked and threaded with lyrics, breath, and tears. Mothers, grandmothers, stepfathers, and lovers enter and exit the pages, while the poems’ speaker sings and shouts and whispers words of violence and love, sex and loss, grief and drowning, miraculous surrender and rescue, forgiveness and faith. Structured as a song, with verse and chorus leading to bridge and ending in outro, the collection is shaped from memory, family, and diary entries and layered with distant islands, children lost, backseats and pregnancy tests, self-love and God’s work. As author Catherine Barnett writes, “Diannely Antigua’s “Ugly Music” is a beautiful disturbance of erotic energy … [a] seduction both intellectual and physical … [and] at its deepest song … a theological protest and investigation by a speaker wrestling with faith and fathers, with unapologetic desire.”

Antigua was awarded the Jack Kerouac Creative Writing Scholarship from the University of Massachusetts Lowell (B.A. in English) and a Global Research Initiative Fellowship to Florence, Italy from NYU (MFA in Creative Writing). She has received additional fellowships from CantoMundo, Community of Writers, and the Fine Arts Work Center Summer Program. Her work has been nominated for both the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net Anthology, and her poems can be found in Washington Square Review, Bennington Review, and elsewhere.

I want to save the girl.

I want to save

the boy.

I want rain on this.—Diannely Antigua, “Self-Portrait as Nostalgia”

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: Diannely, in your notes following the poems of “Ugly Music,” you speak of songs that inspired, lyrics that were borrowed, as well as the use of musical form and theme. Tell us about the collection’s overall structure, and how, for example, French musician and composer Yann Tiersen’s “Comptine d’un autre été, l’après midi” led you to the beautiful, sorrowful motif of “save the girl” in “Self-Portrait as Nostalgia” and elsewhere.

DIANNELY ANTIGUA: The overall structure of the book follows that of a song, with sections entitled Verse, Chorus, Bridge, and Outro. I wanted to ride the emotional frequency that a song can create, how it rises and falls, how it draws a listener in, how an octave change can make the heart ache. I felt this aching in Yann Tiersen’s song when I first encountered it in the French film “Amélie” and then later when it emerged a second time after a fellow poet sent a prompt to write a poem inspired by the YouTube video at the end of her email, and there was that piano again.

I remember listening to the song countless times before ever writing a word. I was breathing in the melody, exhaling something that I could only label as a tortured nostalgia. Then I just started typing, leaving areas of white space for the song to keep living. I began how most love stories do, with characters, “Something with a girl. // And a boy. // Or a father and daughter.” And I told their stories, the intertwining narrative, the overwhelming desire to live and unlive the past. And the speaker undoes and redoes that very past, negating but also affirming the events: “We can mourn things // that weren’t meant for us. // I can tell a lie.” But what follows are a series of undeniable truths—a childhood of playing with pigeons, of being hungry but sharing food, of the boy and the father who leave and come back or maybe they don’t. The speaker wants to “save the girl” from the trauma that she will experience, to let her live a little longer in the “fort made out of sheets,” but ultimately she can’t. Her life must be played out as it was intended. She must experience the hurt that will follow. Just talking about this poem brings tears to my eyes, because it is a surrender, a surrender to the fate that will unfold for the speaker as the book continues.

… the begin-

ing of a secret thing, or that we

reached for each other, a fumbled jazzof grips, on this solstice in June.

—Diannely Antigua, “Golden Shovel with Solstice”

DAVIDSON: Your poem “Golden Shovel with Solstice” reflects a mirrored vertical reading (down the right-hand margin) of Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem “We Real Cool.” The collective speakers of your poem share in discovery and desire, silliness and secrets, especially in their “fumbling” experimentations, echoing Brooks’s lines “we sing sin” and “we jazz June.” How does this poem communicate with the other poems of childhood in your collection?

ANTIGUA: Correct. Many of the childhood poems are about experimentation and the effects of these enlightenments. In “Golden Shovel with Solstice,” the speaker and a group of friends find her mother’s sex positions book, and there is playful innocence in learning how to pleasure and receive pleasure. Though at the end of the poem, there is a tinge of guilt as the speaker reflects that all those involved would now deny the music of that communal sexual experience.

It goes without saying that most of the poems about childhood revolve around themes related to the body (particularly the female body) and how it can be an instrument for both violence and joy. The poem “Beauty Lesson,” for instance, recounts a moment when the speaker learns about her worth, that it comes from her body, as she watches her mother’s beauty regimen of placing a piece of Scotch tape onto her forehead as a way to prevent wrinkles. And the speaker imitates this same remedy, as she tries to forget her abuser, the man who is soon to be her stepfather. We see the mother treat the stepfather with unflinching devotion, and the speaker inherits a complicated truth about love. As the speaker develops into womanhood, it is evident how beautifully dangerous these inherited lessons become.

He says you should be a music

Plucked out of happiness.—Diannely Antigua, “Diary Entry #4: Atonement”

DAVIDSON: Undoing, atonement, testimony, body, bargaining, navigating, prognosis, regression, revisitation. Diary entries multiply and resound inside this soundtrack until we hear second-person declarations like, “You’ll fall on the world like an ugly music.” Speak to us of these entries, their progression, their denial and confession, their truth, their lies.

ANTIGUA: The “Diary Entry” poems are meant to mystify and clarify at the same time. They are the product of an ongoing collage project based on language collected from my old journals. I’ve been writing since I was nine years old—recounting first crushes, my religious devotion, and then my increasing symptoms of depression. Although the resulting poems are based in facts, their truth is found more in the emotional. “Diary Entry #9: Undoing” is the first entry in the collection and it illustrates early experiences with understanding death and grief. The speaker questions the process of properly burying her pet dog but also how to properly mourn the loss her grandmother. Is quoting Psalm 23 at a grave acceptable? What should she wear to visit the dead? Then in “Diary Entry #24: Bargaining” (named so after one of the five stages of grief), the speaker has learned different ways of coping, as her “two-day lover” “slinks off [her] silk” and she finds solace in being used and using another.

The “Diary Entry” poems are limitless. They can encompass any world, whether dream, past, present, or future. The poems follow a progression from adolescence to womanhood, as they track both the speaker’s sexual and emotional journeys, the trauma lived from her innocence to her experience. The speaker who learns “what dream-speak can do to a virgin” in one entry grows into the woman who “wants to sweat,” and the speaker who believes “all SSRIs suck” learns to understand that she is “chemical in a way.” These entries are witness to the cycle of growth and regression, denial and acceptance. They take the reader on an emotional excavation, digging deep into one history of survival.

DAVIDSON: “How I Survived: An Erasure” reveals self-loss, anxiety, association and disassociation, diagnosis, the “snake loop of opening up,” and the realization of being “naturally sad.” There is the element of surprise and the beauty of unmasking in erasure poems. What prompted you to discover the poem that lived inside the Glamour Magazine article?

DAVIDSON: “How I Survived: An Erasure” reveals self-loss, anxiety, association and disassociation, diagnosis, the “snake loop of opening up,” and the realization of being “naturally sad.” There is the element of surprise and the beauty of unmasking in erasure poems. What prompted you to discover the poem that lived inside the Glamour Magazine article?

ANTIGUA: The initial impetus for the erasure poem was an assignment in my MFA class at NYU with Matt Rohrer. At that point in the semester, we were studying the craft of erasures, not only their magic but their rules. I was beginning to feel comfortable using language as building material, etching away at words to reveal a hidden truth. I looked to what material I had in my room and found a stack of Glamour Magazines by my door. The article “How I Survived the Worst Depression of My Life” caught my eye. It followed the stereotypical narrative of mental illness and the road to recovery. It felt stale, and I wanted to shake it up, read between the lines, if you will. And what I found was a more vulnerable and honest version of the original story, one that allowed for victory and failure in the same breath: “When I’m at the edge, // I fall in to stay balanced.” Now the speaker became a voice I recognized—my own. And the two narratives existed side by side, one hidden in blank space, the other now visible in ink.

If I could hold that decade of church in my palm,

I’d grip it like a teacup, or pie cutter from Sunday dinner,

the Lord’s work of licking frosting from a finger.—Diannely Antigua, “Songs of Babylon”

DAVIDSON: Church and prayer and God become sensual at the collection’s center, in the bridge’s introductory poem “Songs of Babylon.” Faith falls, “godlike,” on apology, the promise of a psalm, “the holiest of days,” “my altar and my little fists,” “seeing the shark flag and still jumping in.” Tell us about these lessons.

ANTIGUA: For a decade, roughly from nine years old to nineteen, I belonged to a Pentecostal church. I was devout, dedicating my formative years to Jesus, following a strict set of living standards that infiltrated all aspects of my life. I was repressed—intellectually, creatively, sexually. The more repressed I became, the more I craved. And I craved Knowledge. Not without immense guilt, I rebelled, gave myself permission to gain small scraps of Knowledge from the secular world. But the residue of my former life remains. In many ways, I am still the sixteen-year-old girl who sang in church, who helped serve dinner to the congregation every Sunday, who was saving her “virtue” for marriage. My poems are riddled with religion because it is the language I know best. I can still quote the Proverbs I learned as a child. For better or for worse, the Scriptures live inside me. All I can do is allow them to have their space on the page. But I’ve learned to subvert and pervert them, practicing a freedom that religion never gave me.

You’d know midnight

but not the way you were taught, notafter the cracked tree branch, leafless in his fist.

—Diannely Antigua, “Some Notes on Love”

DAVIDSON: Ideas of love are at times translated into a language of violence, of negation—“not laughing … not running … not breath’s ribbon.” Eventually, they appear as dysmorphia, depression, “awkward courage … lonely power … how the moon appears even in the morning, a pale thing drowned in blue sky.” One begins to wish only the best kind of love, a happily ever after for the speaker of these poems. Tell us about this world, this love, the kind of love wished for and “kissing my hand.”

ANTIGUA: Oh love, how it torments the speaker. How it torments me.

But going back to an earlier answer, the speaker learns these lessons of love, violence, and the blurred lines between from witnessing the mother’s unhealthy relationships, experiencing early sexual trauma, and being a product of both a religious and secular patriarchal system. The speaker carries an inherent belief that she is unlovable and damaged, so she settles for casual encounters and abusive relationships. Sex is a currency she understands, as she exchanges it for moments of artificial intimacy. But truly all the speaker wants is to be accepted and loved as the sad girl, as the complicated girl, as the girl who both longs for and rejects the traditional offices of being a wife and mother. As much as the speaker looks for outside love and affirmation, truly what she needs is buried within her—a self-love, a self-forgiveness. I think RuPaul said it best: “If you don’t love yourself, how in the hell you gonna love somebody else?” Although, I see the truth in this statement, I believe that the unhealed heart can still find love, can still love in return with a fervor like no other. And what is it to be fully healed anyway? I, much like my speaker, am learning how to heal the vulnerable parts of me perceived as “too much.” But in truth, I will always be “too much.” I will always be partially unhealed. And I am learning to find the magic in that brokenness.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor