Kate Bush’s Mind of Winter

Tom Hertweck

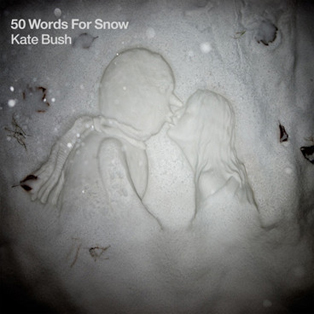

Kate Bush, “50 Words for Snow”

Fish People

2011, 7 tracks, multi-format

Somewhere along the line, as she was completing her career-spanning re-workings project “Director’s Cut” (released in May 2011), Kate Bush latched onto, as many school kids do, the factoid about there being some fifty words for snow in Eskimo culture. Out of this interest, and of her own idiosyncratic way of seeing things, comes her remarkable new album, “50 Words for Snow,” a collection of frosty stories told in a somewhat challenging and darkly jazzy key.

Somewhere along the line, as she was completing her career-spanning re-workings project “Director’s Cut” (released in May 2011), Kate Bush latched onto, as many school kids do, the factoid about there being some fifty words for snow in Eskimo culture. Out of this interest, and of her own idiosyncratic way of seeing things, comes her remarkable new album, “50 Words for Snow,” a collection of frosty stories told in a somewhat challenging and darkly jazzy key.

Of course you have heard of this snow-word business, maybe even passed it on yourself. As the logophile David Wilton points out in “Word Myths,” the factual part of this anecdote is more or less true, depending on how one sorts out the categories “Eskimo” (ambiguous and usually wrongly applied) and “word” (do multi-word phrases and metaphoric deferrals count?). Then again, the same abundance of snow-words holds true for pretty much any other snow-enduring culture. You can come up with a handful of snow-words in English that aren’t terribly out there right this moment—just try. More important, Wilton corrects, is the cultural weight of this fact: what ends does this linguistic accounting serve? In the Eskimo case, he explains, it usually performs the function of relegating native peoples of the north into a category of exotic otherness, an ideologically and politically vexed space, where that inability just to say “snow” in a recognizable way places “Eskimos”—usually an awkward placeholder for any of the indigenous inhabitants of the polar circle—outside the mainstream order.

Bush’s response is instead to mine the plurality of snow signifiers as a resource for seven highly creative musical excursions. Indeed, there is nary an Eskimo to be found. On the title track, a spoken-word conceptual piece, the linguist Dr. Joseph Yupik, voiced by Stephen Fry (yes, that Stephen Fry, in an appropriate turn at the linguist’s tiller), makes a numbered list of fifty different words for snow that span languages across the globe, including some manufactured by Bush herself, and is urged on by Bush’s other-worldly vocals. The song lays bare the terms of how the album sees snow and how snow works on the imagination. Number thirty-nine, for example, “groundberry down” is as compelling and suggestive as they come, calling to mind the way in which snow dusts over the land and, when soft and new-fallen, looks entirely continuous with what it lands on, as if it were, in fact, the gentle outermost of winter’s tiny fruits. In this way, snow, perhaps the most fragile and fleeting of weather phenomena, where it is but a visitor, becomes the locus of imaginative play.

Imagination, of course, comes easy for Bush, as anyone who has taken even a passing interest in her work has noticed1; and “50 Words” makes no exception. A total aesthetic package, the physical album itself is presented as a child’s hardbound storybook, illustrated by specially commissioned photographs of bas-relief snow sculptures that allude to the facing-page lyrics. The seven tracks range from just under seven all the way to thirteen-and-a-half minutes, marking the first time Bush has let songs move into the long-form. Whereas, in past work, the thing that had likely most impressed listeners was Bush’s ability to infuse the short-form pop song with ecstatic yet aggressively complex melodies and esoteric subject matter, “50 Words” emerges out of the snows of its title, awash as it is in blankets of ambient sound from her hand-picked backing band and Bush’s piano. The songs themselves seem to warrant these longer journeys. In “Misty,” perhaps the most magical and fully-realized narrative on the album, a young woman sings of building, making love to, and then yearning for her melted snowman paramour.2 In “Wild Man,” the track that edges closest to being radio-playable, Himalayan climbers encounter a yeti; while, in the book, a Nepalese Buddhist monk looks over yeti tracks. In “Lake Tahoe,” rather than rendering the rime of frost on and around a lake known for its seemingly depthless clarity, Bush tells the story of a mythical lady of the lake who calls after her lost dog.

Always one to extend the boundaries of her own musical craft in a charming and an often moving DIY way, Bush has also produced a number of videos to accompany three (so far) of the tracks (for “Lake Tahoe,” above, as well as for “Wild Man,” and “Misty”). These are not proper music videos, per se, as they interpret only a segment of these longer songs. Furthermore, in being titled differently than the songs from which they are excerpted, the clips offer Bush an opportunity to further explore how our many and varied responses to snow attenuate how we see the world and speak of our own experiences.

What unites the album, then, is what we might call (borrowing a bit from Peter Høeg), “Kate’s Sense of Snow”: an evocation of a weather event that puts one into a reflective mood, that opens up a space for wonder and terror, of loss and longing. The time-traipsing romance of “Snowed in at Wheeler Street”—featuring a much-appreciated and somewhat surprising guest vocal from Elton John—crystallizes that sense, putting two confounded lovers in a mood to think back over their missed and near-meetings across the centuries.3 At the same time, however, it is this sense of snow as a kind of precipitation that covers over the world and obscures it from view that dislocates the songs from their places, a paradoxical relationship that Wallace Stevens so clearly described in his 1921 poem, “The Snow Man,” where the mind in winter “beholds / Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.” Snow, in the way that Stevens uses it and that Bush picks up for her song, is the specific and local cause of the lovers’ being tucked away together; and it draws the world and memory into sharper focus while also obliterating any sense of place in that moment; the song, after all, does not offer any useful clues as to where this Wheeler Street is, other than a place where snow could, meteorologically speaking, occur.4 Furthermore, the song’s narrative dips and glides throughout time also unmoor it from place and serve to remind us of snow’s power to stop and quiet the mind and soul, to take us out of time, a kind of magic that has the chaotic potential of either driving to the center of peace and discovery (think the recent Tom Gilroy–directed R.E.M. video for “It Happened Today”) or driving us mad (think Jack Nicholson in “The Shining”). Snow pervades the album in this way, drawing out time, and pulling in, variously, anxiety in the Himalaya and giving voice to snowflakes themselves (in “Snowflake,” the appropriate album opener). And despite its subject matter, “50 Words” is not a cold record—indeed, it is warm, almost inviting, in spite of the losses frequently catalogued, lush in its orchestrations and the spaces Bush allows to grow in the midst of them—and can be enjoyed precisely because it begs the listener to pause and consider a world wiped cleanest white, silenced by snow’s cottony presence.

It is Bush’s expansive and poetic—in the deepest meaning—sense of snow that I appreciate the most about this album. I want desperately, as I find the record ending and the last notes of Kate singing solo at the piano fading out, to walk out into that whiter world, alone but not lonely, as she says, among angels. That is a hard thing to do in Reno this winter. It has snowed only once this season, with average temperatures rarely dipping below 50 degrees, and that surprise flurry melted away by the afternoon. We have had so little snow, not just on the valley floor but also in the Sierra where the snowpack hovers around 20% of average, that there are legitimate fears about water shortages in the coming months—not to mention the more immediate problem of lost tourist revenue from the simple fact that there’s not much to ski or snowboard on. What I wouldn’t give to cover the city over and think of nothing and let my imagination trip across these achingly silent streets. For now, though, I will simply have to let myself have only a mind of winter, as Stevens put it, with which to appreciate the ups and downs of the present—and this fine album to accompany me.

Notes:

1 Recall her literary flight of fancy in penning a pop song about “Wuthering Heights”—a number-one hit in Britain, mind you—that begot not one, but two different videos that are just as difficult to connect to the eponymous novel now as in 1978, being essentially interpretive dance performances, while at the same time being entirely enjoyable. Recall, too, that she pre-Gaga-ed Lady Gaga by going all Boris Vallejo and dancing with (not playing) an upright bass.

2 Between the storybook format, the dark-but-not-haunting images, and the song’s subject matter, it is impossible not to think of the track as a version of the 1982 cartoon adaptation of Raymond Briggs’s children’s book, “The Snowman,” inflected by an adult romance—so much so that I almost find it an egregious mistake that Bush did not have David Bowie guest on the track.

3 In fact, the song bears more than a passing resemblance in content to Dan Fogelberg’s 1980 AM radio hit, “Same Old Lang Syne,” which some corporate DJs insist ought to be played during the holidays on those stations that switch from whatever flimsy format they are eleven months of the year to being all Christmas music—even though the Christmas aspect is, first, wrong given that it’s a New Year’s song and, second, just a backdrop against which the song’s narrative is set. Both are, actually, songs about snow, plain and simple, and love lost, with Fogelberg’s snow even turning to rain in the final line to hammer the point home.

4 But, really: if you can recall your lover in the moment Rome burns, during World War II, and also in the terrifying aftermath of 9/11, why not be snowed in on Wheeler Street in Houston or Los Angeles? (To be sure, this desire to find out where Wheeler Street might be is a subject of much discussion.) One, too, thinks here of the expression “to be snowed under” as a metaphoric expression of being overworked or overstressed—what else could this be but both the cause and consequence of unrequited love?

Tom Hertweck is a PhD candidate at the University of Nevada, Reno, where he is completing a dissertation on post–World War II American food literature and culture. He is still waiting to build a snowman this year.

0 comments on “Review: Hertweck”