Inheriting The Earth:

Digging Deep With Trio

A review by Jonathan Lawrence

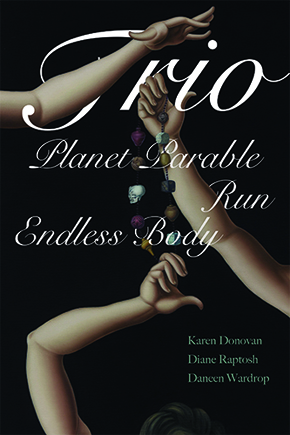

Karen Donovan, Diane Raptosh, and Daneen Wardrop, Trio: Planet Parable, Run: Victoria Woodhall—A Verse History, Endless Body

Etruscan Press, 2021

246 pages, softcover, $20.00

Three complete books of poetry encased in one binding: this is the gift the reader receives when looking at the cover of Trio. The cover art, Jesse Mockrin’s Ritual consists of three almost-bodies—three arms circling around a necklace as each individual arm seems to continue out beyond the page. If these three “bodies” are the three distinct poets and their work, Karen Donovan, Diane Raptosh, and Daneen Wardrop, it is a necessary question to ask why these three poets have placed their work in conversation with one another. These collections are read as singular entities, yet are entangled, operating in tandem to bring about new ways to think of language and poetics in conversation and community. To enter into these three distinct collections is to search for what makes them distinct on their own, as well as make discoveries of which threads bring all three poets together by the close proximity of the page.

Three complete books of poetry encased in one binding: this is the gift the reader receives when looking at the cover of Trio. The cover art, Jesse Mockrin’s Ritual consists of three almost-bodies—three arms circling around a necklace as each individual arm seems to continue out beyond the page. If these three “bodies” are the three distinct poets and their work, Karen Donovan, Diane Raptosh, and Daneen Wardrop, it is a necessary question to ask why these three poets have placed their work in conversation with one another. These collections are read as singular entities, yet are entangled, operating in tandem to bring about new ways to think of language and poetics in conversation and community. To enter into these three distinct collections is to search for what makes them distinct on their own, as well as make discoveries of which threads bring all three poets together by the close proximity of the page.

Planet Parable the first book in Trio by the poet Karen Donavan expands the quotidian, the scientific, the philosophical, and the ordinary into a compacted and tight lyrical exploration of the earth. From Donovan’s poems, the earth embraces human existence through lyrical osmosis, and that power is present from the book’s natural imagery.

Diane Raptosh’s Run rediscovers the life of Victoria Woodhull, a prominent businesswoman, suffragist, feminist, spiritualist, and radical. Not only did she run for president, but was an advocate for the “Free Love” movement. Through this reformation of history, Raptosh utilizes a multitude of poetic forms to trace Woodhull’s life, and the individuals that intersected her existence.

Trio rounds off with the book Endless Body by Daneen Wardrop. Utilizing somewhat seamless transitions from poem to poem, Endless Body traces the speaker’s loss of her mother, as well as the birth of the speaker’s own daughter. Wardrop crafts perspectives on what this cycle of life can provide when dealing with grief, confusion, and cosmic significance.

All three collections of poetry have distinct strengths, yet the collaboration, and conversation(s) between the works bring about a necessary triad of poetry each creating different notes in themselves. Each poet brings endless modulations to the distinct, spiritual and even rebellious voice of the feminine within their pages.

Karen Donovan is at her best with poems that hit the reader with tight-knit couplets. Prior to the first substantial section, her mini section, “:Upon opening the archive” brings the reader into the book with a scene of a woman operating a backhoe:

Dewy city, digester of asphalt,

true scribe and library,labyrinth text, vault of clouds.

the meadow is not a blank page.The woman at the controls

knows this. Now she raisesthe complex orange arm

of the backhoe, as her own,articulated at the wrist and aware

of itself when tested againstwhat desires to resist

form, impeccable gestures

Within the literal aspects of this scene, Donavan challenges the reader to excavate the metaphorical connection of earth and humanity. The tight knit couplet poems create rhythm and give a timbre that flows, or stops with clever caesura and punctuation. Donovan asks the reader to raise the question to themselves, in what ways has the earth inherited the human quotidian?

Donovan is never afraid to expand to different forms, and the reader is granted gifts like the poem “I Saw Egrets Flying.” Donovan continues with the beautiful repetition of bird imagery that courses throughout the entire book, and gives a view of animal, human, or social flight. This poem submerges itself in a sort of meta-poetics; “I saw a print in the sand and wondered if it was possible to mention that in a poem.” This prose poem is an interesting switch into the world it inhabits, but meditates on the stillness of image itself, and the lists of images that pass us by as we read while Donovan’s speaker “was in my head but also outside of it.” The setting of this poem invites the speaker to ponder the complexity of nature and memory, in the movement (and stillness) of our existence and days.

Planet Parable offers a multitude of subject matter stemming from the connection of nature, to philosophers like Wittgenstein, to the microscopic observations of crystals, and DDT. Donovan’s stanzas, and sometimes near-iamb meter, open these pockets of magma, marl, and metamorphic sections, a homage to the geological churnings of the earth. Her poem “How You Are Exactly Like a Zeolite” is absorbent in itself:

Quick

throw your body hard

against a wall and flatten

to a sail, fill with hurricane.

You are the catcherand the caught

a force that twists

the instant, wringing free

one rare, one bitterelement, that pure,

that red, that

hum. You’ve heard it

now. Receive.

With the utilization of indents to bring tight quatrains to a flowing pace, sometimes interrupted with lyrical pauses, this poem presents what Donovan attempts to do in these poems: the creation of a field of consciousness, a look into the mundane, scientific, and natural until the earth has re-inherited what humans have so long taken granted of.

While the reader is still attempting to encompass the cosmic quality of the first book, Diane Raptosh’s “Run” presents a fascinating reanimation. By taking something out of Donovan’s book, there is an excavation of the life of Victoria Woodhull. Raptosh’s utilization of experimental forms that jump from poem to poem give light to the radical, compassionate, and determined spirit of Victoria Woodhull. Raptosh’s usage of form opens these (purposefully) forgotten archives of Woodhull’s life, to grant a look into a prominent Suffragette.

Woodhull’s resume is expansive, and Raptosh utilizes masterful research and a hold on form to present Woodhull’s philosophy, “which aims/to open up/agency./She encouraged/a female invasion/of masculine precincts—”

Short lines craft this poem as the spirit guide of Odessa Claflin (Victoria’s dead infant sister) speaks. Not only does Woodhull’s fight for equality transcend into the spiritual, a multitude of characters intersect this aspect with the radical vigor in which Woodhull presented her politics, and lifestyle.

With the behemoth of a personality that Raptosh encapsulates through her poems, what stands out most is the urgency of this book to come to print. The poem “Victoria’s Stump Speech Psalm” transcends history to the many intersecting narratives painted today by intellectuals, politicians, or random opinion-havers alike:

Be kind to the new.

In freedom

is safety. When people

learn this, they’ll know equality …

Caste stands as boldly out in this country …

The false relations of the sexes

resolve into dependence of women

to men for support.

By contextualizing this poem within the historical narrative of the book itself, Woodhull’s philosophy of fighting for our “unalienable” rights, which weren’t given to women at the time (yet are so entrenched in the political philosophy of our nation), and other marginalized groups alike, brings the reader to view the current times with a new perspective. Raptosh brilliantly forges a further understanding of social movements and their growth. This poem’s immediacy and wisdom pins the reader to the ideological, even physical battles our country seems to rehash, reconstruct, and regurgitate in favor of the powerful. However, with the reincarnation of this voice, comes the staunch rebellion and determination needed in order to craft an even more just and open world.

Like many revolutionaries of their time, Woodhull was also met with aggressive censorship in the realm of public opinion. Characters within the book, like Susan B. Anthony and Pauline Wright Davis, reinsert Woodhull exactly where she needs to be, even though the individuals listed above distanced themselves from Woodhull. Through the personas of Susan B. Anthony, Pauline Wright Davis, and others, Woodhull’s legacy is reanimated. Raptosh utilizes these personas to shed light on Woodhull, and to re-energize the work she did for the Women’s Movement during that time. The persona work in this book tells another side of the Suffrage Movement, and speaks to the injustice suffered by Woodhull herself in relation to some of her beliefs. Raptosh’s use of several forms, like a clashing of different narratives with physical breaks in the middle of lines to create a chaotic energy of a spirit beaten down.

The Epistolary poem “Dear Victoria” presents an alternate view of Woodhull’s beliefs and her colleague’s response, “and that at all times/truth is dearer to me/than anything else/but there are times/when silence/is all there is.” What is it like to be an individual so entrenched in a social movement, yet so seemingly radical by their colleagues that history has literally redacted them? There are several poems struck through in order to present the redaction and silencing that many of Woodhull’s allies began to utilize against her.

After finishing Raptosh’s book, I am left with sadness. Yet, Raptosh chooses to break history, with a final poem titled “Out and.” With a loose hexameter that fades away within itself through near and perfect rhyme, Woodhull becomes “a newfangled arrangement of atoms.” Raptosh eventually reinserts references to Woodhull within the poem, and re-creates the spirit of a Presidential nominee and activist through formal and lyrical means.

Daneen Wardrop’s book Endless Body utilizes not only musicality as a metaphor, but the usage of dropped lines, and experimental stanzas that sprawl across the page to give an endless nature to her poems. The mother-daughter-mother relationship that transcends from the speaker’s loss of her mother, to the raising of the speaker’s own daughter, brings the reader in contact with an array of connections within several lifetimes.

Wardrop makes apparent the formal and stylistic choices of her poetry. Each poem needs to be seen as well as read:

We are not stopping, not counting

in this place where divisions happen faster than breaths.

Wardrop masters the pause in this collection of poems, whether that be the clever use of punctuation or placement of lines on a page, or the repetitive dashes that end (but simultaneously) begin her poems. These line breaks create the stillness and depth of Wardrop’s lyrical verse, but with the creation of the “body” that is morphed into one. One of the book’s first poems, “Stir the lake” is a sweeping meditation from a Guitar Workshop Camp on the Puget Sound, reaching into the holistic body of the collection: “The book in my lap reads: god in the minimal and the maximal.” Wardrop’s mixture of line length can stop, turn, even twist the reader to see the world and the speaker’s connection not only to her kin, but to the world and universe in itself.

Even with Wardrop delving into what seems like the personal at times, the sentimental is held respectfully within these poems. Wardrop’s poems become more absurd, imagistic, and surreal, but never lose sight of their corporeal interconnection:

I can’t give a personal biography—

a parade,

where balloons, buildings-high,

must be tipped to fit under traffic lights.

With Wardrop’s utilization of the entire page, the poems make sense of loss through a lyrical, and spatial awareness. Poems continue into others, with italic titles and character usage to bring the reader through the fluid folds of each poem’s structure. This way of compiling the text helps continue the familial connection, sometimes so clearly as, “A mother lives in again.” Wardrop’s ability to craft this “endless” body through the usage of continuity by structure, brings about a sense that our loved ones, mothers, daughters, etc. although may leave us due to death, still create this substance and sustainability of familial memory, thus living “again” through another’s existence and memory.

From self-titled caesuras, which infiltrate the reader’s mind with characters like the ancient poet Caedmon, to Emily Dickinson entering the page for a few poems, Wardrop’s work increases and wanes, and intensifies back to where it started, within her poem “Vast – vast- +,” whereas in “How to rewind the lake …” the reader is gently dropped into the endless body of lifetimes as the voices of her mother and daughter are interwoven with the speaker’s. Wardrop raises an invigorating question in her final poem, “At what rip in the gravity do we enter?” Regardless of specific entry points, “Endless Body” immerses the reader into the whole of the cosmos. From the personal universes, readers, the speaker, the mother, and the daughter contain, the poems wash over readers, like the coolness of a lake, into the universe of utterly human: vulnerable, beautiful, absurd at times, but whole.

Clutching a book with three entire collections of poetry might seem daunting for some readers. However, the ability to read one “book” at a time opens versatility in the way this Trio can be read. The energies that each contain, along with their spiritual similarities, there is no question why these books were paired together. The collaboration and teamwork between all three poets is admirable, and aids in the success of each book. Cento poems fashioned by the poets themselves, conclude and introduce each book. Through the combination of lines from all three poets the connection is apparent, these books not only stand on their own, but have been in conversation for quite some time.

No matter what order a reader chooses, each collection needs to be read as a whole, in order to gain access to the microcosm that is each poet’s distinct language and style. Whether one starts from the back, middle, or front, a reader will begin to craft connections throughout the collection as a whole, which makes the reading all that more satisfying once one has finished. Enjoy reading each individual collection as a container in itself, but the journey through each of these poet’s worlds then expands and compounds one another, where a reader is left feeling the need to connect back to the earth, to history, and to the connections our relationships infinitely craft throughout time.

Jon Lawrence is a poet and from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He currently teaches tenth grade English and Creative Writing and is an MFA student in the Maslow Family Graduate Program in Creative Writing at Wilkes University. He can be found on Twitter @JonLawrence1116

Jon Lawrence is a poet and from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He currently teaches tenth grade English and Creative Writing and is an MFA student in the Maslow Family Graduate Program in Creative Writing at Wilkes University. He can be found on Twitter @JonLawrence1116