Meredith Stricker’s Anzaldúa Poetry Prize winning chapbook “Anemochore” is truly beautiful and inspiring. From her unique and layered title “Anemochore,” to her intricate design and use of space on each page, Stricker offers as much insight and perspective from their placement of her words as from their meaning.

“Anemochore” keeps no borders between visual art, poetry and even music. Stricker’s work here demonstrates a melding of ideas that flow naturally from page to page, evoking all of a reader’s senses.

Meredith Stricker fuses her work with her own experiences, including performances with musicians, her own work as an architect in Big Sur, California and her deep perspective into the value of poetry and imagery. The second part of the chapbook, The Be/s of the Invisible, was a collaboration with several other musicians that link the life of bees to the freedom in poetry.

Her chapbook “Anemochore” will be published by Newfound in spring of 2018.

Steve Mulero: When did you begin writing poetry and what were some of your influences on your early journey into poetry and art?

Meredith Stricker: Because my mother was a war refugee for whom English was a second language and my father’s family from Russia spoke in an archaic form of German, I grew up

in a household where several languages mingled in ways that were basically incomprehensible to me, except as a kind of music or rhythm that was deeply familiar, but also untranslatable.

Whatever one could call “normal” English was not a given since even the language my mother taught me had an accent. And so much remained unspoken. So, it always seemed natural to swim in the space between words. You could say poetry and imagery were a first language for me or a kind of mother tongue.

Also, there’s really no “normal” language for any of us. Which is why poetry matters so much in its rejection of “normalizing” in favor of the particular and odd and nearly inexpressible which we all hold in common in entirely different ways that poems, our senses and imagination can access.

I remember going out on the hillside where I lived in Oakland and talking to the trees and birds in this kind of in-between language. I have always been drawn to forms of poetry and image that are multi-lingual in this way and can be read inside and outside of English in ways even birds could understand.

How do birds understand us or we understand them in a poem? I don’t know, but somehow the poem knows.

“Anemochore” simply extends this process.

Mulero: The title of this chapbook is “Anemochore,” defined as a “plant that spreads seeds or fruit by wind.” Why did you choose this for your title? What tone and feelings did you want to elicit from the reader of your work?

Stricker: It’s a beautiful and odd sort of word. The Anemo– or wind part carries the sense of Anima also related to wind, soul, breath, spirit, so this felt important. And then it seemed to take the shape of a bee swarm or bee language forms that are core to the second part of the book, The Be/s of the Invisible.

Mulero: Is there a musical element throughout “Anemochore” as well? You include “adj. anemochorous / wind chorus dithyrambic polyspecies lyric” and in a later line, “are you a wind instrument are you breath / gone wild.” These lines emit a type of wild musicality. Is there a play-on-words to be found with the term Anemochorous?

Stricker: Those are really interesting questions. Yes! Music is very much part of this book.

All of The Be/s of the Invisible was created as a collaboration with musicians, bee-keeper and another artist for a performance in Oakland. I worked with musician Kumi Uyeda, and two other composer musicians using several kinds of instruments: piano, accordion, tonkori, cello, toy piano, melodica live with recorded voice, electronic music and video. I added visual projections and then half-sang, half-read the poems as a kind of chant.

The audience also was part of sound with a participatory score based on lines of the poems. In terms of these specific lines you mention, you’re asking questions that tune into sounds, which speak to how we hear as much as see a poem.

How reading a poem is multi-sensory: seeing-hearing-sensing.

I am particularly interested in the communal and performed sense of poetry. And here, the -chore of Anemochore sounded to me like the chorus of classical Greek where lines where spoken/sung and danced (choreography/chorus). Poetry was always mixed-media, multi-genre across many cultures. Performance brings this sense of chorus into current practice.

So, “polyspecies lyric” pretty much sums up the intent of book itself and probably the hopes of all of my current writing.

Mulero: Do you feel there is a comparison to be made between an anemochorous plant and how its seeds disperse by wind and how individuals spread ideas through language and their own voice?

Stricker: Yes, absolutely. Writing and visual art for me are more of a kind of open-ended research than self-expression and what I keep discovering is how the page is itself a field or habitat where the word-seeds move and that our lives, spoken and unspoken, are intrinsically interwoven with the lives of seeds, plants, rivers, clouds, weathers.

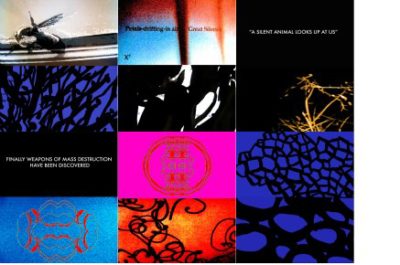

Mulero: How did you come to the photos and artwork in “Anemochore?” What is your artistic process when merging both poetry and artistic imagery?

Stricker: I always work with visual work in relation to writing. I don’t separate them. Even the shape writing a poem is more like a gestural drawing than a statement, say in filling in forms or information. Also, the written images in poems are continuous with images made of India ink, paint, collage, video and three-dimensional objects. There are the materials of the page and book then also installations in gallery space and performance.

There’s always this slippage between the verbal and non-verbal, gesture and sound, world and word.

The photo at the start of “Anemochore” comes from a performance at night in a field I did with dancer and collaborators. The movement of the light suggests writing or a kind of hive, which fits my sense of the book.

The Be/s of the Invisible came together when my friend Kumi said let’s do an hour-long performance in a few months and I noticed I was working on poems and images related

to bees and colony collapse disorder and that I could use these as projections throughout the performance. I made drawings and paintings of patterns of bee-flight used in communicating flower location to the hive. And these were projected and used as a graphical score in the performance. There was a lot of color; bees see colors — some of which are out of human range. Poems and images help us to see outside our normal range, closer to the vision of bees.

Mulero: The way you utilize space on certain pages offers a unique imagery of its own. Sometimes the words drip off the stanza and onto the next page. What inspired you to utilize such distinct formatting and design?

Stricker: I work as an architectural designer as a partner in a studio mostly on coastal sites in Big Sur. You make drawings or shapes that start on a two-dimensional page related to a living site with grasses and earth then translate the ink into built forms. We work with not only Euclidian geometries but also fractal forms leaves, shorelines and more, breaking the pre-set forms of a rectangle to curve or jag with the coastline.

This is very exciting! As we talk, I’m realizing how similar the page is to a landscape.

I mean, there’s actually a lot of space on a page. The white space is not just a backdrop for written lines any more that a landscape is the background to drop in a pre-set house design that doesn’t pay attention to the shape of the land, the existing biotics, the weather or light.

In the same ways that the words and phrase structure can move in relation to the voicing and shape of intuited thoughts in a poem’s physical surface.

In “Anemochore,” I began to discover what felt like fractal or dendritic forms the way tree roots and branches are patterned. And the Be/s of the invisible are meant to move like hive swarms or individual bees foraging.

Also, there’s the animism or livingness of the poems themselves the desire of the lines themselves as though these words want to bend or break off. Others need more space. They seem to want to exist as their own beings. And when you can feel and relate to that being, the poem or page feels complete.

Mulero: Do you feel that there is something lost in translation when words like “wall” (which you mention in the catalog of synonyms on page 11) are spoken only in reference to it’s the physical sense?

Stricker: Working with the habitat of the page as with other environmental work is political and communal. “Anemochore” addresses the brutality of the kind of Border Wall the current administration is attempting to force on us, or the Separation Wall imposed on Palestinian communities by Israel or gated communities or the Iron Curtain which separated my mother and countless others from their homeland and free movement. Also, the futility of any Authoritarian Wall. Or the utterly mistaken idea that we can wall ourselves off from the fate of honeybees as we use harmful pesticides or dump toxic materials into the biosphere and not poison ourselves:

“I’m breathing your oxygen you’re breathing my carbon dioxide

green world blue world red world my darling permeable membrane

there is no greater love than this

folded in involutes” – Meredith Stricker

I would not draw a line between human and other speech, say of trees or owls or at least I would hope to bridge that divide through poems, art and living with senses open.

Mulero: Do you have any advice for aspiring artists and poets?

Stricker: First to notice is everyone is aspiring, which kind of relaxes the pressure. No poet says to herself “Yeah, I’ve totally made it and know exactly what to do next….”

Also, just to write and make images on-goingly without expectation. Even for small amounts of time to keep the thread of your work alive in the midst of everything (self-doubt, drive for productivity, demands of paying jobs) that tries to pull you away from trusting what shows up on your page.

And be willing to work unstintingly, without measure. Poems may appear instantly outside our conscious effort but they are not efficient.

Bring everything in: sounds, scribbles, words, wordless. Bring in notes, spaces, noise. Then sieve out. It’s quite physical like sorting beads, feeling resonances.

Track the energy of your work: read aloud to self or others: keep the parts that feel alive, take out parts that feel wordy and grey (no matter how much you loved the ideas of them)

Hearing the poems outside the loop of your own mind helps clarify immediately.

Step out of your habits: work in collaboration with others. Find a band of poets, artists you can exchange work and perform with. Not as a big deal, just playing poetry, the way musicians play music.

Trust. Allow. Make things. Connect with others.

Stevie Ray Mulero graduated from Georgian Court University in May 2017 with a Bachelor’s Degree in English Creative Writing. An avid reader of poetry, plays, novels and short stories, Steve intends to transcend the way we consider ourselves and others, life, loss and reality.

0 comments on “Anemochore: An Interview with Meredith Stricker”