Words So Odd and Ordered: An Interview with Karin Cecile Davidson

Margo Orlando Littell

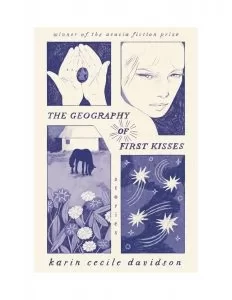

Parents and children, husbands and wives, the newest of acquaintances. No matter how intimate the relationship, people find ways of both connecting and damaging one another, and the harm is intentional just as often as it is offhandedly cruel. Love, death, hope, and heartache play out across the country in Karin Cecile Davidson’s story collection The Geography of First Kisses, winner of the Acacia Fiction Prize. The landscapes that serve as backdrops to these characters’ lives are varied and richly rendered, and readers familiar with Davidson’s prose from her debut novel Sybelia Drive will recognize its evocative poetry in these stories. But make no mistake: the beauty of the lines is gentle cover for the emotional evisceration she examines here.

“French toast, he calls it. He is from the heartland and doesn’t understand his mistake, that the French would never call this toast, the importance of words and meanings as lost to him as the sad rusks of baguette he dips in a bowl of beaten eggs and cream and nutmeg.” –from “Skylight,” page 23

MARGO ORLANDO LITTELL: Though some of these stories are set in glittering cities, others are set in less glamorous locales—Tulsa, Oklahoma; Columbus, Ohio; Dynamo, Iowa. What inspired you to use these places as settings for your stories? What about them sparks your imagination? And how do the various locales work together to shape this collection–its geography, if you will?

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: Place is pretty much where I begin in stories. Somewhere for my characters to stand, to feel their feet strike the ground, to understand the roll and curve of a road from the seat of a Harley or the cab of a Ford truck. Another starting point is the memory of where I’ve stood so that I can portray a story’s setting with as much detail as possible. There’s always the research one can do to carry the idea of location, but having been there in person creates another kind of picture altogether. Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Columbus, Ohio, and, well, not Dynamo, but an idea of Dynamo, Iowa—these are places I’ve visited and lived.

Tulsa surprised me. I was swayed as much by the sight of oil rigs across the Arkansas River on what had once been Cherokee land as by the city’s Art Deco architecture, the Praying Hands of Oral Roberts University, and the Golden Driller at the Expo Center entrance. I think I wrote that Tulsa story, “We Are Here Because of a Horse,” so I could live there for a while, if only in my mind. I was completely taken with the city.

I live in Columbus, an incredibly livable city, which lies within the easterly swath of fly-over states and the part of Ohio that is topographically uninteresting to most but holds the secrets of ravines and multiple watershed systems, as well as a thriving art and cultural scene, and some amazing places to eat and drink. “Skylight” was written when a good friend dared me to write an Ohio story, convinced I couldn’t do it. I won the dare but cheated, not entirely able to leave New Orleans and the Gulf Coast out of the narrative.

And I once lived in Iowa, but not in the fictional town of Dynamo. The state was as golden as it should have been—sun, corn, pigs, smiles, and even the Amana Colonies with their giant farm breakfasts and woolen mills and rolling fields.

To me, these places seemed perfect settings for stories, and to be honest, I didn’t set out to write the pieces to be part of a collection. Rather, they called to be written, and in the end had similar themes—searching, longing, hoping, loving. Think of that barn scene with Howdy in “Sweet Iowa,” when he’s surrounded by tractor parts, tools, the Allis Chalmers manual, and the heavy scent of hay. Something as mundane as a barn isn’t mundane at all; it’s rich with possibility, all those details, right? Then add in tornado weather and the-stranger-comes-to-town complication, the stranger a Texas high-plains woman searching for a particular kind of pig. The reader might think, Really? So, yeah, Iowa works.

As far as these stories and the shape of the collection, I think they’ve created an atmosphere of Americana. A few stories travel as far as France and Berlin, but mostly they lie within the sweep of states from the Gulf Coast to the Plains on up to the Midwest. Like the patchwork of a quilt, perhaps one made from old blouses and damask tablecloths and faded denim and even Carhartt overall pieces, the stories and their locations are very different, nevertheless connected with indigo thread and patterned with the determination and direction of the characters.

MOL: There’s a kind of love letter to Louisiana couched within the violence of “The Biker and the Girl,” where the biker–usually moving from place to place–explains he always wants to return to Louisiana because it “felt truer, heavier, something he could understand.” For your characters, or for you personally, what about Louisiana, or the South in general, exerts this gravitational pull?

KCD: I spent my childhood in Florida and Louisiana, the beaches and bayous practically our backyards, places where we swam and went fishing and crabbing. Travel within the states and beyond and understanding other cultures has always been important to my family, and there was always the act of returning home. Eventually, the idea of home changed, a university career anchoring us in a landlocked state, but New Orleans and the Gulf Coast kept calling me back. We had family there, so visits were possible, but the idea of returning home evolved.

By way of writing, I’ve been able to return. I’m constantly returning to that riverbend corner where the biker meets the girl, to Florida backroads, to the old Highway 90 that connects the gulf states. There is something, after all, about the places where one begins, where formative years are spent, where one forms a foothold in the world.

Many of the characters in the collection are infused with a sense of place, of belonging—like Antoinette in “In the Great Wide”—or of yearning to be somewhere else, namely the place they started out—like Chloe in “Skylight.” Add to this the idea of home and its complications, how a nostalgic sense of place is not always realistic, how families aren’t always easy to return to, how a city’s infrastructural failures might seem like adventures to a child but are challenges to an adult. In the end, it’s the sway of New Orleans that still calls and my characters that get to answer those calls.

“Celia recalled how her father had read poetry aloud to her mother. How her mother would lie back on the couch and listen, and Celia, still awake in her room, would listen too. Words like chicory, daisies, restlessness–words so pretty, so odd and ordered, still echoed inside her.” –from “Soon the First Star,” page 92

MOL: The devil is in the details, the saying goes, but in these stories it’s the soul that’s housed in the details. Specifics pile up across these stories, and within the stories; often, whole paragraphs are peppered with nouns as simple as they are evocative. In the first pages of the title story, for example: “the beaches were covered with rocks and sea glass and broken pottery” and “the metallic breeze carried traces of brackish water, diesel fuel, rubber boots.” Lines like this have their own rhythm and their own poetry. What images do you feel are most important in this collection? Which images were your guides as you created these stories?

KCD: The most important images? I suppose I don’t grant one more importance than another, for each story has its own, and there are many, that’s true—an imperfectly beautiful coastline, a flickering drive-in movie screen, the silhouette of a horse gone missing, jet trails seen through a skylight, a winding river road, the satellite image of a category 4 hurricane, a strand of pink rosary beads, the stunning sight of blue crabs, a courtyard crowded with books, the bristled golden back of a Tamworth pig, the brilliance of Cassiopeia on a December night, the depth of a gorilla’s gaze, milk-carton sailboats sent out into floodwaters, the fragility of a quail egg. The layering of tone and texture arrives out of images. The narrative of a teenage girl wanting more from life and getting more than she counted on arises from coastlines and sailing and desire. That of a woman caught in an abusive marriage is examined through an afternoon with her children in the ape house of the Berlin Zoo. The story of a young girl, sent to spend several months with relatives in the Mississippi countryside while her mother is hospitalized in New Orleans, takes on the attempt to understand how life and death are related.

Oyster shells, azaleas, halyards and half-hitches; scratched jazz records, a hidden bruise, a Voightländer’s shutter release; cotton sheets, a wooden ruler, a small speckled egg. With the collection of images, the bigger picture emerges, the story taking on color and spectacle. Throughout the drafting, it’s really the characters who decide on their images; I just go along with their desires and then provide descriptive details that create scene and tension and forward movement. There’s an act of trust here, following along in what seems like the dark to me, but obviously is completely lit-up and clear to these fictional personalities.

“‘Come on,’ he says. ‘Seriously, how can a person live in a city for nineteen years and not call it home?’” –from “Skylight,” page 22

MOL: Many characters in this collection lack rootedness, lack even the desire to be rooted or the knowledge of how to become rooted. In “Skylight,” Chloe has lived for nineteen years in Ohio without feeling like it’s home. In “One Night, One Afternoon, Sooner or Later,” a girl wonders how long she’ll want to stay in the bayou. Tell us how the theme of wanderlust–or dissatisfaction–shapes the characters in this collection.

KCD: Thursday’s child has far to go, right? Seems to be a theme in my writing, in this collection. Whether they’re feeling emotionally and/or physically removed from the place they want to be, or challenged by the place they’d like to escape, the characters seem to find a way. To survive where they are, to embrace their surroundings, or to consider flight. In “Skylight,” the story written on a dare, Chloe finds a way to stay in Ohio, to feel content, but whether her solution is imaginary or real, well, that’s up to the reader. After all, shouldn’t one question the existence of Gus Van Sant, a pug named Lily, a Super-8 camera giving her reason to track the rest of her life? And in “One Night,” in truth a tale of revenge, what about Lors, poor confused Lors? Hers is the angle of a super-complicated triangle that seems to lose its sharp definition. She’s tested by her relationship with both Jude and Micah and with each of them separately, enough so that, despite all the fun they’ve been having, she doesn’t know if she can stay. Yearning for what was always familiar, longing for something that’s new and within arm’s reach—these desirous situations occur again and again, the characters having to negotiate rough territory, not just geographically but intellectually, as well as by way of their egos and desires and recollections.

“He had to consider the value of recklessness in a world that moved too slowly.” –from “Sweet Iowa,” page 56

MOL: In “Sweet Iowa,” farmer Howdy is drawn to a strange young woman who appears in town, a woman who attracts attention when she tosses a pig over a bar–she’s reckless in a way that captivates Howdy. But accepting this woman into his staid life is a kind of recklessness too, opening up a new set of possibilities for Howdy’s future. Do you think recklessness is always an opportunity for transformation? What other characters are impacted by rash decisions or unexpected paths?

KCD: Recklessness might be seen as the antithesis of routine, and Howdy’s life is nothing but routine. What Morgan brings him is another dimension of what is considered routine, and perhaps that is what disturbs him by the story’s end. Lors’s reckless summer makes her question the direction she’s been taking, but her considered transformation is off the page. Antoinette’s flirtatious route toward becoming an unwed mother definitely transformed her, but is it recklessness that causes her baby daughter Daphne’s transformation? Perhaps recklessness doesn’t always lead to subtle change or deep metamorphosis, but in these stories, there is evidence of just that.

“I could tell by her hard, questioning stare that she’d never seen a bodiless baby before. And Daphne hadn’t always been this way. In fact, I was just getting used to it myself.” –from “In the Great Wide,” page 75.

MOL: “In the Great Wide” is a story that carries its surreal elements as casually as you might carry a handbag. The narrator, Antoinette, reacts to the “slow disappearance” of her baby with concern, but there’s also a suggestion that this sort of event is no cause for alarm; she compares her bodiless baby to a “bright, child-size bowling ball.” Tell us the origins of this story, and how you came to tell it with such a stunning degree of matter-of-factness. How did your writing process or approach change when confronting this story, if it did?

KCD: “In the Great Wide” was written after Hurricane Katrina as an homage to New Orleans. Sometimes one writes stories that come out of a helplessness that is bound with love. When I was growing up in 1960s and ’70s, rainstorms constantly tested the city’s drainage pumps, and when a hurricane came to town, even just to skirt the area, the streets were flooded. These were the kinds of floods we rode through on our bicycles, not the kind that created mass devastation. After Katrina when the pumps failed and the levee breached and the city lost too many souls, New Orleans pulled herself up mostly of her own accord, with no thanks to government assistance. The city had the mind to rebuild, and slowly it did, but in the meanwhile, it didn’t have the body to get things back to where they’d been. Too much had been lost, folks had to grieve, many left or were forced to stay away. It took years and then decades to see normalcy again, the spirit of the city challenged but persevering.

Hence, bodiless baby as metaphor.

It’s strange to think that I had no idea what I was doing when attempting the first thoughts and words of the story. The process took years with a lot of resistance, and though Antoinette questioned her faith, I had faith in her, and so I pushed her character harder and harder. And she pushed back. Add to this the fact that I hadn’t lived in New Orleans for decades, though family and friends did, and the pull of place, especially this place, remained strong. By the fifth draft or so, I recognized what was happening. A city already veiled in fabulist threads, it didn’t seem beyond believing that in this fictional New Orleans cream-colored roses could appear overnight from sidewalk cracks, bowling alleys might be mysteriously draped in fishing nets, a baby’s body might diminish until all remaining was her sweet little head. And that Antoinette could be, as you’ve pointed out, “matter of fact” and in near denial of her baby’s slow disappearance. Her refusal to reveal her true panic is heavily clothed in how she questions faith, her Catholic upbringing, and in the end, I followed her where she wanted to go. The story is her journey. She is rebuilding her life, and life is dealing her a deck of cards that’s missing more than a few cards. She’s more than a bit jaded, and while she understands that miracles happen, for her the truest miracle is her child.

MOL: An element of carelessness mars many of these stories, in that adults fail to offer or fulfill appropriate care to their children. There are adults who yell in “We Are Here Because of a Horse”; adults who leave in “Soon the First Star”; and children buffeted by illness and tragedy in “Bobwhite.” Parents are a child’s primary landscape. Why are you compelled to examine characters who faced its decimation?

KCD: Most of my writing veers toward what is realistic, and in real life, wayward parents or those who are more concerned with their own reflection do exist. I’m interested in the landscapes that children come up with and gravitate to when parents are less attentive, even neglectful. There’s the adage among writers, “give your characters trouble,” right? And there are those characters we bump into, begin writing, and then wonder, Whoa, what happened to you? This would be more the case with Meli in “We Are Here Because of a Horse” as she is now an adult and still dealing with the neglect and seeming abuse of her elders. The fact that she changed her landscape early on by following a horse she’d sighted from her bedroom window and that she is still searching for that horse is compelling. Celia in “Soon the First Star” and Carly in “Bobwhite” have their landscapes changed for them, as their true parents cannot care for them, and so, others do instead.

I think the word “decimation” reveals a lot about these characters. There is destruction done to Meli’s childhood, but she resists and holds onto the spirit that, in essence, keeps her alive. It’s heartbreaking how many children in this world must survive their own childhoods. In her story Meli is still surviving hers. In “Soon the First Star,” Celia’s self-destructive mother sends shockwaves into her child’s world. I wanted to examine this through Celia’s viewpoint and see the kind of hurt and anger she felt. Thank goodness there’s rescue for Celia when her mother’s childhood friend Nicki steps in.

Decimation is also defined as “the culling of wild animals,” and here I can also reflect again on your question about images as guides when creating these stories. I remember watching a friend’s teenage brother defeathering and dressing bobwhite quail when I was about eight or nine years old, Carly’s age in “Bobwhite.” This image stayed with me over decades, and I wanted to write about it. Carly and Robbie and their relationship came from this moment, but so much more happened in terms of exploring death through a child’s eyes, especially as it appears when pinned up against life. The idea of the hunt and how the tiniest bird went from flight to death and eventually dinner was a gorgeous, terrible thing to examine, to define and try to give reason. Cast this inside a hazy Mississippi autumn in which a child is sent away from her New Orleans home because of her mother’s failing heart. Studying the connection of life and death from a child’s perspective is challenging, and yet I went there.

MOL: This collection follows your debut novel, Sybelia Drive, and some of its characters inhabit the same landscape. What landscape is inspiring–or might inspire–your next novel or stories?

KCD: I’ve nearly finished drafting a novel that covers a lot of landscape not yet approached in my previous books. I had been working on another story collection set—of course, where else?—in the Gulf Coast states, and I had a few stories completed but felt dissatisfied. So I began an entirely new story which wasn’t a story at all, but this novel, in which a character from one of those stories showed up, only she wasn’t a teenage girl but a woman in her thirties embarking on a road trip. The working title is Highway 61 and covers ground from Grand Marais, Minnesota, all the way down to New Orleans, where that highway ends. I love how the Mississippi River and its tributaries run alongside this highway nearly the entire way, and yes, I’m still returning to New Orleans in my fiction without even meaning to.

The inspiration for the project came from Jessica Lange’s beautiful book of black-and-white photography by the same title. For each photograph I wrote a paragraph and eventually for clusters of photographs taken in New Orleans, I wrote scenes. The photographic inspiration evolved into a fictional world for which I studied maps and details of towns, many of the places already known along with their trees and birds and contrasting topographies, from white pines to live oaks, from chipping sparrows to great blue herons, from Lake Superior to the Gulf of Mexico. Oh, and throw Florida in, because I just couldn’t help myself. In the book’s beginning tones, think of a tempered version of Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage. Structurally, think of Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies. Then add in a good amount of love and loss, and don’t forget recklessness, an old Ford Fairlane, biology, fraternal twins, and a band called The Lovers. I must admit, I’ve loved writing this book. It’s nearly there!

Karin Cecile Davidson is the author of the novel Sybelia Drive and the story collection The Geography of First Kisses, winner of the Acacia Fiction Prize. Her stories have appeared in Five Points, Colorado Review, Story, and elsewhere. Originally from New Orleans, she lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Karin Cecile Davidson is the author of the novel Sybelia Drive and the story collection The Geography of First Kisses, winner of the Acacia Fiction Prize. Her stories have appeared in Five Points, Colorado Review, Story, and elsewhere. Originally from New Orleans, she lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Margo Orlando Littell is the author of the novels Each Vagabond by Name and The Distance from Four Points. She lives in Pittsburgh.