Pinprick

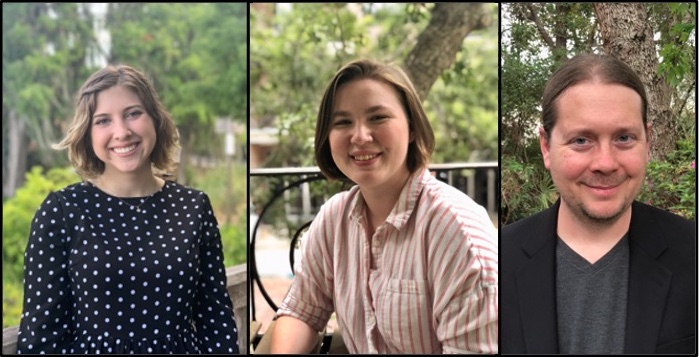

by Hannah Butcher, Kendall Clarke, and Matt Forsythe

A pinprick of guilt leads to stabbings.

Corina shivered beneath the layers—a sheet, a quilt, and a calico blanket her great-grandmother had stitched. Perspiration gathered on her forehead, beads of ice. It was the middle of summer, but her sweat was unnatural.

She hated the fever, the way it melted minutes into hours, muscle convulsions and chattering teeth. But the bubbling pit of nausea at her core was unrelated to her illness; it was the guilt of forcing her daughter into the role of caretaker. Lydia had enough to worry about as mother of her own child—playing nurse, cook, maid, friend, nanny. And now, with Corina buried beneath this avalanche of cloth, Lydia was expected to perform doubly. There were groceries to get, dishes to soak, a toddler to soothe. All while Corina lay helpless, unmoving.

Guilt is also an avalanche, isn’t it?

Her thoughts had slipped into metaphor after the doctor banished her to bed, concerned at the onset of fever after surgery. She had nothing to do but read and sleep and remember. And what was there to think about? The extra work she brought Lydia. The planting season she was missing. A body that refused to heal.

Dust floated where the sun shone through the window.

The day of her accident, she had been thrilled to return to the garden after a long winter indoors. Her arms full of tomato sprouts, she tripped on the back stoop. Her wrist could not support her. Soil rained down. It seemed to last forever.

At first, the doctor called it a bad sprain. She’d been lucky, he said, especially at her age.

Days later, she had trouble grasping the flour in the kitchen, spilling over the bag and dusting the floor with White Lily; yet she was determined to clean it up, knees on tile, wrist throbbing as she swept with a hand broom.

Lydia found her on the floor and sped her to the physician. An overlooked fracture was identified. Her wrist was cut open, scalpel separating skin from muscle, peeled back to reveal her ruby insides. An animal skinned and prepped.

The eight cousins, the specialist said, pointing to her scaphoid on the X-ray. That’s how I memorized the carpal bones in med school.

He listed them: trapezoid, trapezium. . . . She was surprised at the cluster. Like gravel from the driveway, pebbles by a stream—a literal handful, hidden under a paper-thin layer of skin this entire time.

She knew the more obvious bones, like the arm she once cracked in a fall from the tire swing. Or her metacarpals—sources of her arthritis—which now flared from lack of exercise. Trapped in this room, unable to work in the cool spring dirt. Soil therapy, Lydia called it.

Those bones she could feel. But this jigsaw puzzle? It confounded her.

Eight cousins, all buried within her wrist. She fingered the blanket with her unbound hand, an heirloom that would pass to Lydia.

•

Her family once had eight cousins. They grew up like siblings, playing together on neighboring farms, but drifted apart in adulthood, scattering like seeds.

There was Henry, her brother, whose son now owned and worked the farm, living across the field. Silvia moved to Naperville, and Samuel, her favorite, transferred to Florida to work for NASA.

You were always the smartest, Corina had confessed, rocking on the porch during one of his rare trips home. Growing up, I secretly wished you were my brother.

Intelligence and wisdom are two different things, he said. His wife had remarried and taken his daughters to Ohio. Eyes half-closed, he watched the sun settle beneath the horizon, under the cornfields.

Who else?

Tom was murdered in Vietnam.

Rebecca died young, back in the 80s.

Ethan was still alive, against all odds. So was Ruth.

Corina counted with the quilt patches. . . six, seven. Who was the eighth? She racked her brain, upset that she’d lost an important name because if she forgot, who would remember to tell her, who would tell her it was okay to forget?

Oh.

It was her.

Corina was the eighth.

•

Mama? Lydia pressed the back of her hand to Corina’s cheek. You still have a fever. Her daughter’s palm turned and caressed her face. I’m gonna finish supper and let the doctor know, okay?

She refilled the bedside cup with water, pressed the rim to Corina’s lips. She must have swallowed because Lydia stepped away with a relaxed face, the relief and sadness of a duty fulfilled.

Be right back.

Her daughter’s touch reminded Corina that she had a body. She was floating atop some stem, a wispy string connected to fingers and lungs, these vulnerable things.

It is something, isn’t it?

All this time we thought we were the roots of our children. But we are only the leaves.

Hannah Butcher and Kendall Clarke are recent graduates of Rollins College, where Matt Forsythe teaches in the English Department. Their collaborative fiction has previously appeared in Sky Island Journal and The Headlight Review.